Humanoid robots exploit artificial intelligence to become “thinkers” and reduce the emotional gap with human beings

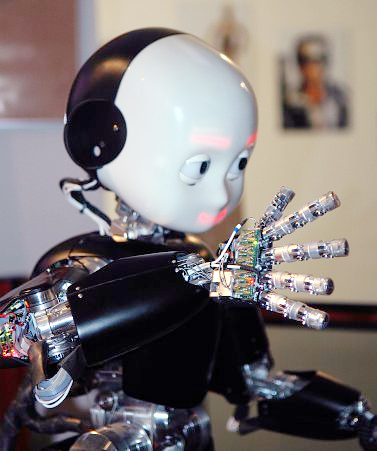

© Lorenzo Natale

That’s what they are called: humanoid robots. Hybrid “creatures”, half-machine, half-man. While hardware is the body and the soul is the software, it is in the brain – alias in artificial intelligence – that the evolution of the species is occuring.

In their veins flow algorithms and billions of bits of data, which do not serve simply to make the robot functional. Artificial intelligence is capable of interpreting information, reacting to it, learning and behaving as a consequence, and even elaborating original solutions. They are becoming “thinking” machines, that can provide answers that not even the human mind can elaborate, not within the space of thousandths of a second, and often not even in a much longer timeframe.

Increasingly similar to man in terms of physical appearance, the new-generation robots are even capable of feeling, or at least simulating, emotions. To the point of confusing human beings themselves, of generating empathy and provoking unexpected reactions. This was proven by the results of an experiment conducted by the University of Duisburg-Essen in Germany: 89 volunteers were simply asked to enter a room one at a time and turn off a robot. 43 of them were not told that the robot in question – “instructed” by the research team – would have pled with them, even implored them to let it “live”. The unexpected plea provoked equally unexpected reactions: 13 people decided not to turn off the robot; the others did, but not immediately.

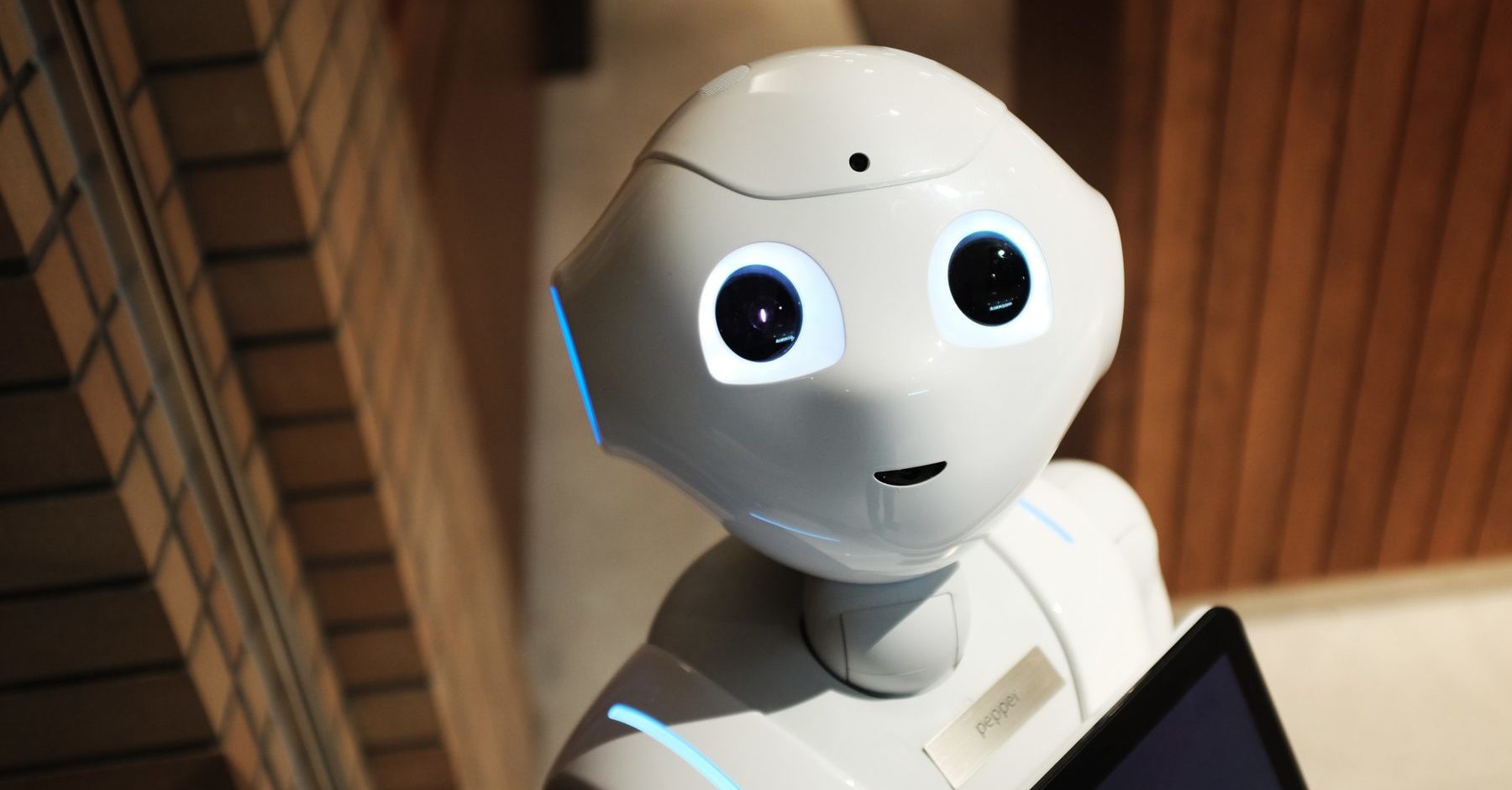

Pepper, the first “social robot”

The result shows that the boundary between man and machine is growing increasingly fragile. And this opens us to sociological and ethical considerations on the implications and the impact of artificial intelligence and the new generation of “emotional” robots. Think of children’s toys: dolls and stuffed animals can speak and even answer – this is the “Siri” model – and will soon be able to “react”, learning from the words and behaviour of children and increasingly adapting to them.

The positive impact is equally undeniable: humanoid robots can become fundamental “assistants” to the disabled and the elderly and can even be helpful in the area of pathologies such as autism, thanks to the empathy generated by their “human” appearance and behaviour.

Humanoid robots already “live” among us, and some of them are so intelligent and humanized that their inventors have earned awards and acknowledgments.

Nao © Xavier Caré

Italy is a leader in terms of the number it has turned out. One Italian invention is Pepper, the first “social robot” created by the Laboratorio di Robotica Cognitiva e Social Sensing at Icar, the high-performance institution of computer science and networks of the CNR, produced by Softbank Robotics. Also Italian is the “brain” of Nao, the first humanoid robot – also produced by Softbank Robotics – that can interact independently with its surroundings. It was created by a joint tem of the Università di Pavia and the Politecnico di Milano as part of the European programme Human Brain Project. And the same EU project led to the creation of iCub, a robot that looks like a four year-old child developed by the Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia (Iit), and adopted by about twenty research laboratories around the world: this robot was the protagonist of the “emotional” test at the University of Duisberg-Essen.

cover photo © Diarmuid Greene

© ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

translation by Olga Barmine