The book by Irene Ranaldi explains what ‘gentrification’ means for residents

English words are often inflated. And sometimes they end up like Don Abbondio’s latinorum, making it impossible to understand what they mean. Gentrification, a word that is now widely used, is one of them. Commonly it is understood as the phenomenon by which a working-class district, sometimes deteriorating, is revitalised when new residents come in from outside, new businesses open up, etc. But reality is far more complex, and most importantly it can be seen from the inside as well as the outside. This is what sociologist Irene Ranaldi writes in her new book ‘Gentrification. A semi-serious guide to an urban phenomenon’. Ranaldi is a researcher in qualitative theory and analysis in the Sociology Department of La Sapienza in Rome, and president of the social promotion association ‘Ottavo Colle’.

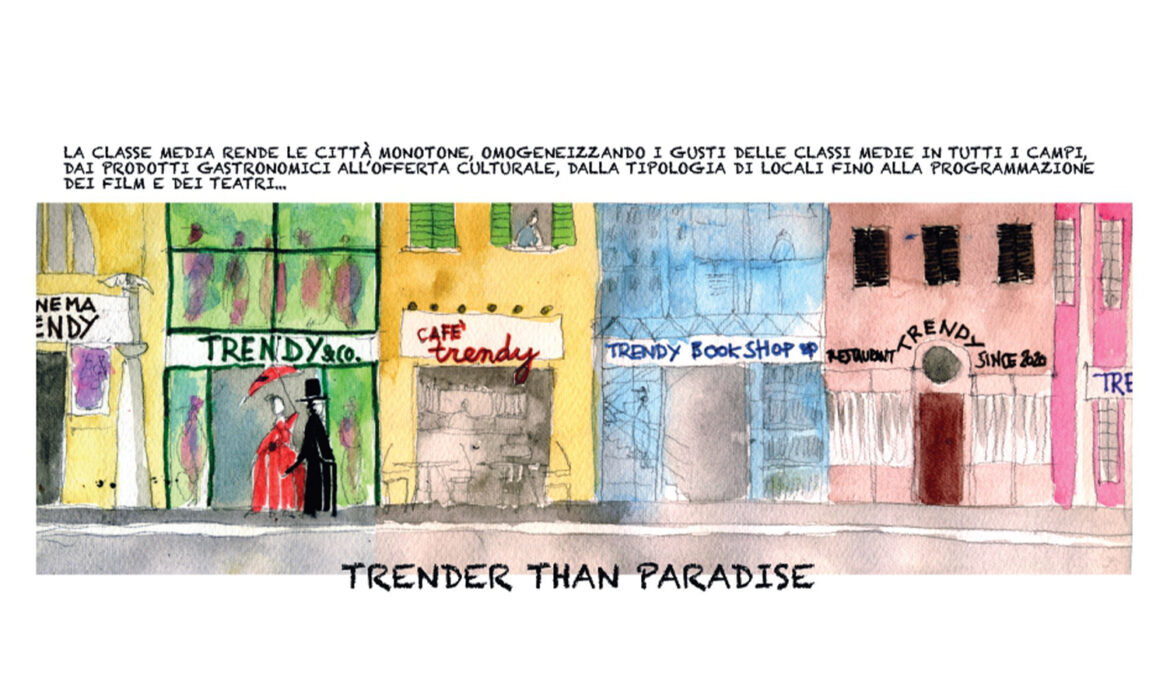

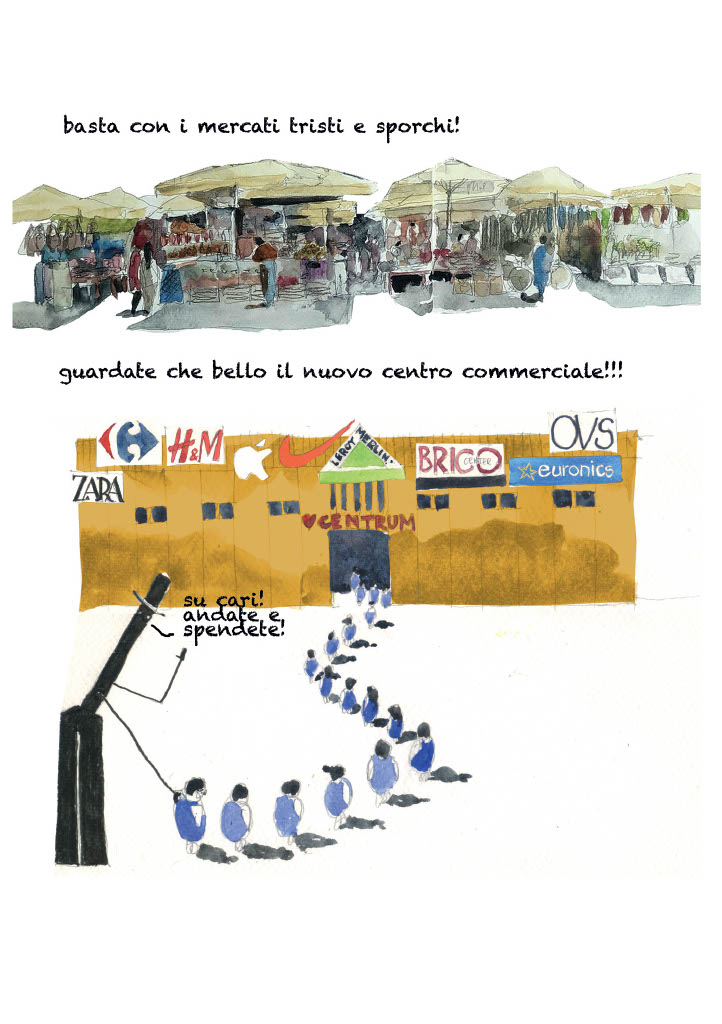

Based on an anthropological and sociological analysis, to which she adds a touch of irony, the author shows us the other face of gentrification, increasingly common in neighbourhoods in larger cities. The term is also used as a synonym for regeneration. But they are not synonyms. Regeneration should involve the people who already live in the neighbourhood, Ranaldi tells us.

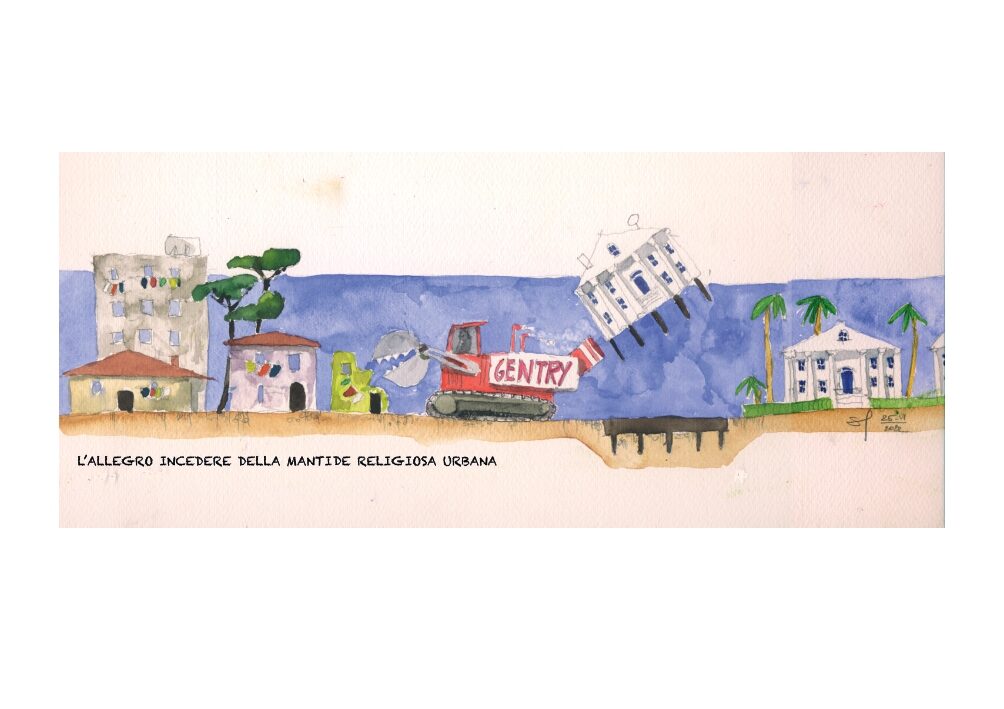

On the contrary, gentrification begins with “commercial” development, due to which at the end of the process the area is no longer affordable for the people who live there, who will progressively be replaced by wealthier new residents.

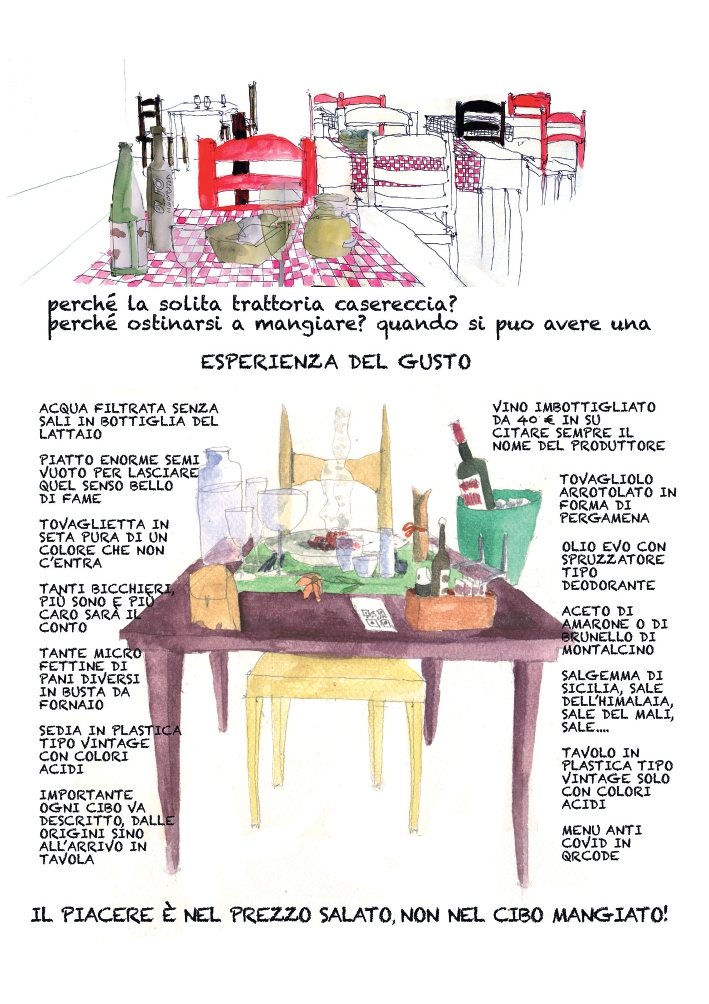

Traditional businesses and family-run stores pay the price, while services aimed at the new residents mushroom.

In Rome, the city where Ranaldi lives, similar phenomena have frequently occurred. In San Lorenzo for example, which was once populated by workers, and has now become symbolic of university students. Or Testaccio and Ostiense, adjacent areas that were once authentic, in the case of Testaccio a sort of suburb of the city centre inside the Aurelian walls. Until they were both overrun by bars and restaurants, theatres, night clubs and sushi bars, becoming hotspots in the Roman movida. Even Trastevere, if one looks more closely, was a case of gentrification, rarely cited because it happened rather long ago. For decades a mandatory destination for tourists and pub crawls, this part of the historic city centre on the right bank of the Tiber River was much different up until the 1980s: of course, not everything was perfect.

It was in Trastevere, in Piazza San Cosimato, that in 1980 the first boss of the Banda della Magliana, Franco Er Fornaretto Giuseppucci, was killed, just to give you an idea what we are talking about. But Trastevere was also the beating heart of old Rome, the city that Claudio Villa, who was born there, sang about (just like Gabriella Ferri who was from Testaccio). And it is no coincidence that one line of the song read: “Progress has made you great, but this city is not the city we lived in so many years ago”. In old-time Trastevere there were trattorias that served real Roman specialities, which in some cases (such as fried brain) might not be too inviting today and are now very hard to find. They weren’t the tourist traps that abound today, which rake in money, like the many b&bs. Trastevere has that vernacular atmosphere, with little or no sophistication, which Carlo Verdone immortalised in the film Un sacco bello, in the episode when clumsy Leo meets the Spanish girl Marisol at Porta Settimiana. But as is often the case after gentrification, the genuine tradition of Trastevere, now gone, is still used as the story of the neighbourhood for marketing purposes. Better? Worse? You can’t take stock like this, off the cuff. But that is the point: gentrification doesn’t revitalise an area, it changes it. Cancelling its folksy working-class spirit, solving some problems and creating others.